by Dr. Sara Hamilton, ORKA Science Coordinator

“At its best, science is a self-correcting march toward greater knowledge for the betterment of humanity. At its worst, it is a self-interested pursuit of greater prestige at the cost of truth and rigor. The pandemic brought both aspects to the fore.” – Ed Yong in “How Science Beat the Virus” The Atlantic, 2021

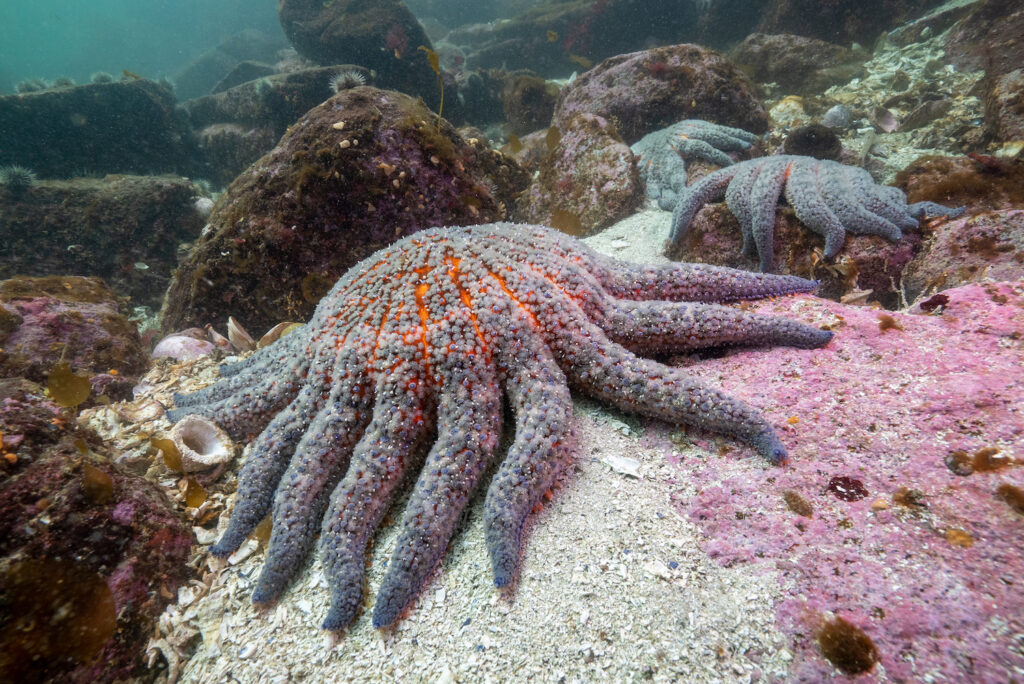

In February 2020, I sat in a conference room at the Seattle Aquarium surrounded by experts on sea stars. The Nature Conservancy had arranged a two-day meeting to bring together scientists and conservationists to identify what could be done to help save the sunflower sea star, which had suffered a 92% decline in populations due to Sea Star Wasting Disease (SSWD). The SSWD pandemic is considered to be the worst marine disease outbreak ever recorded and killed billions (with a ‘b’) of sunflower sea stars. I was quite early in my career compared to most of the people in the room and a little starstruck to be included in the meeting. Dr. Alyssa Gehman, a disease ecologist and author of a recent Nature paper, was there.

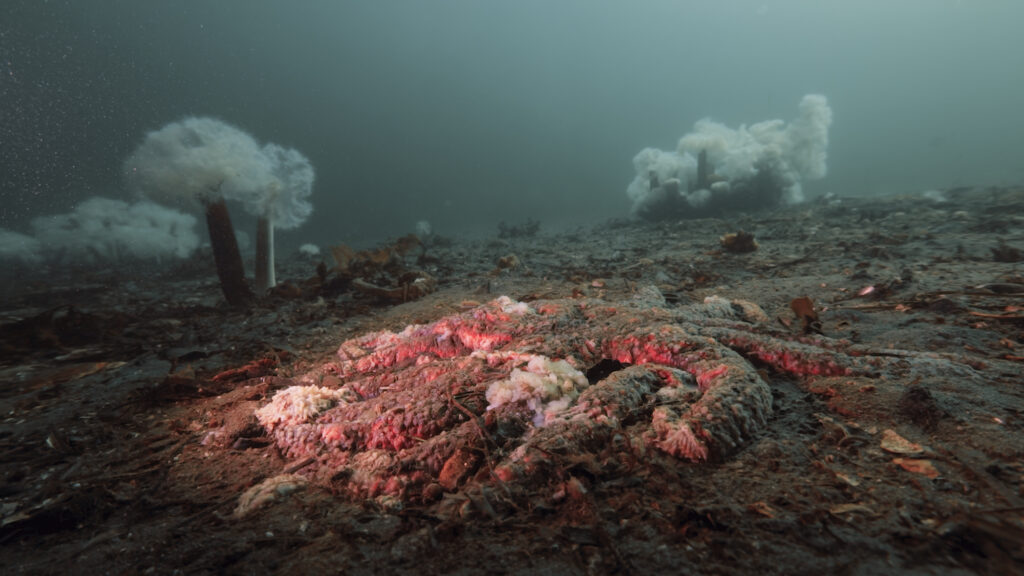

I remember clearly that one of the key outcomes of the meeting was that the community simply had to know what the causative agent of SSWD was to be able to meaningfully support recovery of the species. Any active recovery efforts, like captive breeding or translocations, would have to be done in a way that ensured those efforts did not initiate a new SSWD outbreak. And we could not ensure that without knowing what SSWD actually was. Two disease ecologists at the meeting, including Dr. Alyssa Gehman, were chosen to work with The Nature Conservancy to figure out how to make that happen. A few weeks later, the world, my life, and science as an industry was plunged into chaos as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded.

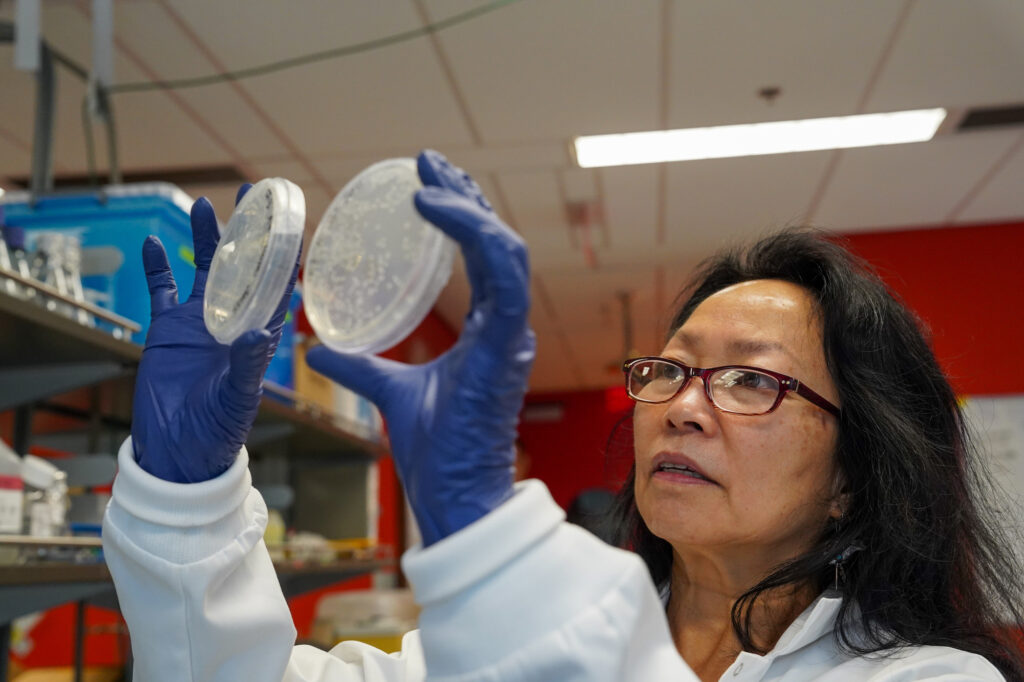

More than five years later, the mystery has been solved. On Monday, Dr. Melanie Prentice, Dr. Alyssa Gehman, and a team of other researchers released a paper in Nature Ecology and Evolution identifying the causative agent of Sea Star Wasting Disease to be Vibrio pectenicida. V. pectenicida is a bacteria closely related to another species of Vibrio that has been plaguing oyster hatcheries in the Pacific Northwest for years. In the paper, the authors outlined 3 years’ worth of experiments that painstakingly pieced together multiple lines of evidence positively identifying V. pectenicida as the culprit.

Monday afternoon I sat in another meeting, a meeting of the Pycnopodia Recovery Working Group, a community of practice that I had helped coordinate and lead when it was incepted in 2021. The mood was absolutely giddy. As Alyssa and Melanie presented their findings, the chat was a constant stream of ‘WOW!’s and the screen raining with applause emojis. Everyone had questions and congratulations for the co-authors.

The finding comes at a critical time for Oregon. ORKA and partners at Oregon State University, the Oregon Coast Aquarium, the Oregon Zoo, and beyond are currently working on promoting sunflower sea star recovery in Oregon. Since 2023, sunflower sea stars have tentatively begun to try to re-establish a foothold in Oregon. Sightings of juveniles have slowed crept upwards. This year, ORKA scientists have collected 24 sunflower sea stars from the Port Orford area and are translocating them to Nellies Cove, a kelp forest restoration site, with scientific permits from ODFW. These scientists will track how well these sea stars adapt to a new home, if the incidence of SSWD changes at all, and how urchins at the site respond to the presence of this predator. Hopefully some of these stars will remain at the site and aid our efforts to reduce urchin populations enough to allow kelp to regrow at Nellies Cove, where bull kelp has not been seen in almost a decade.

In coming years, ORKA and partners are making plans to support sunflower sea star recovery in other ways too. In 2026, we’re planning to work with fishermen to take sunflower stars accidentally caught in fishing gear and relocate them to kelp forest restoration sites. In addition to hopefully helping control urchin populations at those sites, aggregating the stars at specific sites may improve the chance of successful reproduction by keeping stars close enough that their gametes can co-mingle and successful fertilize when they release them into the surrounding water. Additionally, we are writing up on a concrete plan to establish a pilot captive breeding program that could outplant hundreds of sunflower sea stars one day along the Oregon coast, similar to the current program for California Condors at the Oregon Zoo.

All of these efforts will benefit from the new discovery of the causative agent, as well as the test for V. pectenicida that Drs. Gehman and Prentice are already developing. For instance, at the Monday meeting Dr. Sarah Gravem, an ORKA member working on this year’s sunflower sea star translocation efforts, was asking if it would be possible to sample the Port Orford stars and send the samples to Drs. Gehman and Prenctice for screening for V. pectenicida.

When I was contacted last week about the new discovery, I ran out to the living room to tell my husband about it. I had heard that this paper was in development and had been waiting to read it for months. Really, I’d been waiting to read it for years, ever since that 2020 meeting in Seattle. Since February 2020, so much has changed for me and for kelp forests in Oregon. I’m no longer a graduate student, but a working scientist. Kelp forests are no longer an unknown ecosystems to Oregonians, but are the topic of news articles and science pubs statewide and have an entire non-profit working for their preservation. Sunflower stars are again present in Oregon, and I got to see my first sunflower sea star on a dive at Pacific City, one of ORKA’s restoration sites, in 2023.

Some of the most exciting parts of my science career have been related to sunflower sea stars. I have gotten to be involved in exciting new revelations about the species, sitting in my office and being aware that I was holding new knowledge that only a few people in the world knew about. I’ve gotten to be interviewed by national news outlets about my research on the stars. And now I’ve gotten to be a tiny part of the process that led to the discovery of the causative agent of SSWD.

As quoted at the top, the science writer Ed Yong has said that “At its best, science is a self-correcting march toward greater knowledge for the betterment of humanity.” He said this in reference to the COVID-19 pandemic, but it holds true for the SSWD pandemic as well. This discovery is science at its best: passionate people working together to use technology and the scientific process to try to save a species. That’s amazing. It is one of those shining, special moments in your career that make you proud to be a scientist and excited about the future of kelp forests here in Oregon. In a post-COVID world that sometimes increasingly feels filled with uncertainty, challenges, and anxiety, passionate people coming together to try to make some little corner of the world better lights up a path forward. And hopefully, that path forward includes flourishing sunflower sea stars, kelp forests, and coastal communities here in Oregon.