Four score and seve—wait a minute, just kidding! It was 12 years ago that this all started! In 2013, a huge blow to our intertidal and subtidal communities took place: SSWD (Sea Star Wasting Disease). SSWD is a bacterial disease caused by Vibrio pectenicida. This bacterium is a distant relative of Vibrio cholerae, which causes cholera in humans (don’t worry, nobody got cholera this summer!). This epidemic killed about 97% of sunflower sea stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides), a major predator of the purple urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus). This huge loss of predation on purple urchins by both sunflower sea stars and sea otters, which were lost to Oregon in the 1970s, has allowed them to have a dramatic increase in population sizes. The purple urchin’s favorite snack is bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana), which is also the kelp that makes up a huge habitat that houses thousands of species in Oregon’s coastal communities. In recent years, Oregon’s coastal towns have noticed a dramatic decrease in the size of our bull kelp forests and an increase in purple urchin populations. This is because purple urchin populations have grown to an unsustainable size. This means that there is not enough food to support their population without disrupting other species’ populations.

In Port Orford, Tom Calvanese and others founded ORKA (Oregon Kelp Alliance), which is a group dedicated to helping restore our kelp forests along the Oregon coast. There are a few teams working within the ORKA organization, but ours is focused on the sunflower sea star and trying to restore its presence in order to decrease purple urchin populations and subsequently boost our kelp forests’ chances of survival by stopping the urchins from overgrazing them!

The Pycnopodia ORKA team did a ton of work this summer, but like all things, it started with lots of prep work! We began a few months before the field season started, designing and creating cages. This was done with the help and collaboration of the iLab at OSU’s Hatfield Marine Science Center. We spent many hours cutting, perforating, and gluing together our acrylic cages, as well as mixing concrete to make the anchor platforms our cages were attached to. This was all done so we could make sure that the stars were in an environment that worked for our project, but was also physically safe for them in a high-surge area.

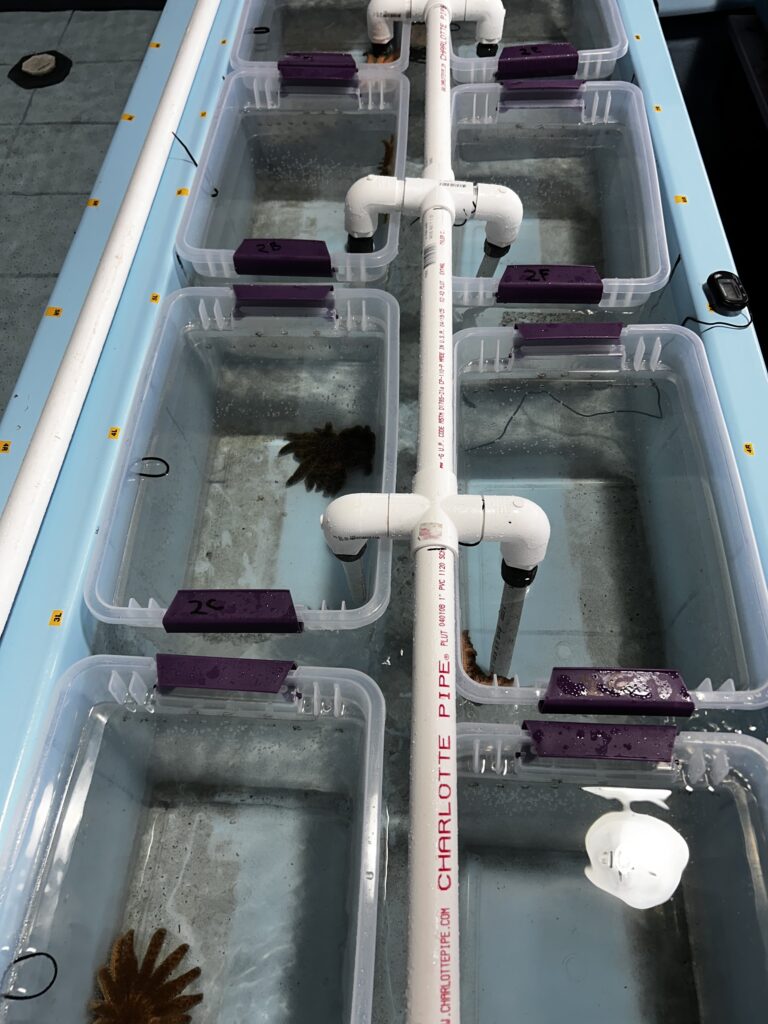

We started collecting stars for the project in May of 2025 in Port Orford, OR, where our project was going to be set. We also needed to make sure that our sunflower sea stars would be staying in good health, so we partnered with the Oregon Coast Aquarium. They were extremely helpful in making sure all our multi-legged friends were ready to be part of our work this summer! After collecting them, the stars were transported to the Oregon Coast Aquarium for a month-long vacation/quarantine to make sure they were all in good health individually to participate in the project.

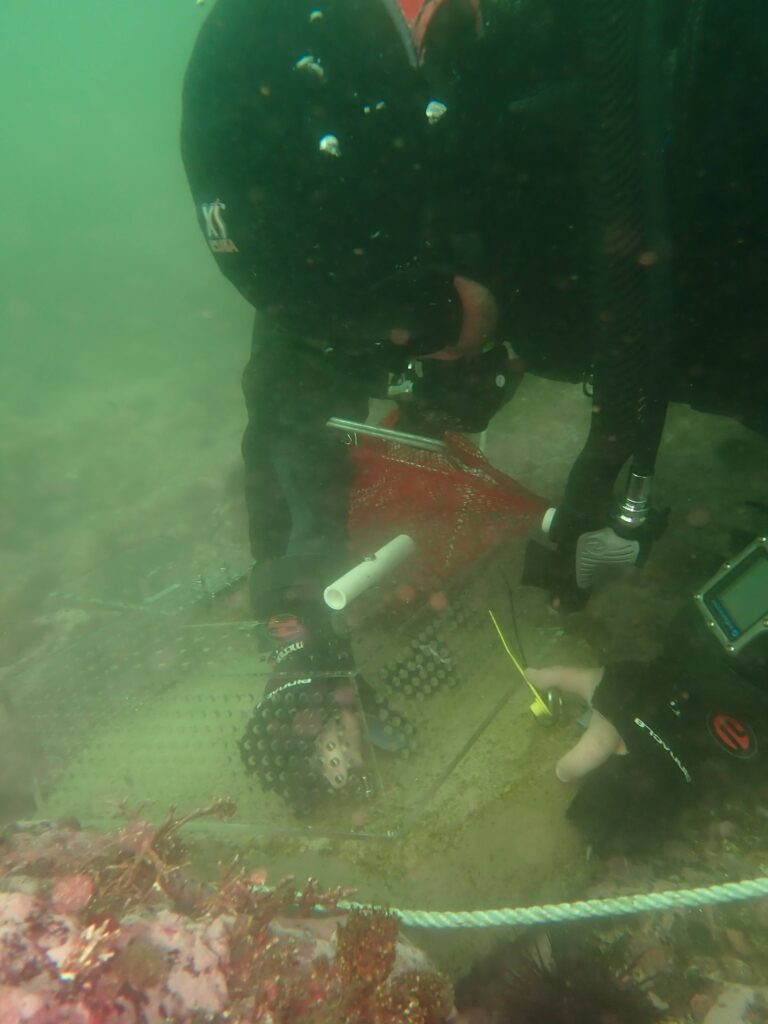

In June, our summer interns, Talia and Katie, moved into the OSU field station in Port Orford. They and the rest of our primary field team (Miles and Kersten) got all the equipment we needed deployed out to our work site off the Hellbow, which is a rock formation just southwest of Nellie’s Cove. Once Casa Constellation was set up, our sunflower stars got all moved in for their month-and-a-half-long beach resort adventure! The Constellation experiment is meant to help us get a better understanding of purple urchin spacing with and without the presence of their primary predator, the sunflower sea star. The work is all done subtidally, so we can best understand the spatial effect that the sunflower star’s chemical cue, which travels through the water, has.

The team would go out three to four days a week to do various pieces of maintenance and run the experiment itself. We would start by going around and feeding everyone a full-course meal of purple urchins, then doing a health check to make sure they were all acclimating well. Then we went to collect bull kelp off the Port Orford Jetty. After collecting kelp, we went back to the lab to prepare everything for deployment the next day. This meant cutting, weighing, and labeling 84 pieces of kelp (way harder than it sounds!). We would hang a bag of all that kelp off the dock to make sure it still looked yummy for all the urchins out there.

The next day, we would collect our kelp and set out to the work site. Our first dive would be to do pre-surveys to look at where the urchins were without the influence of kelp (their favorite snack) being down there. Once we were done with those, we would lay the kelp out on chain lines at specific intervals to see how far out our landscape of fear goes. The next day, we would return and do our post-surveys to see where the urchins had moved to, and then collect all of our kelp again. Back in the lab, we would measure and record the weights of all the kelp pieces to see how much the urchins had eaten over the course of a day.

A few times, we were able to go on sunflower star searches, which meant we would pick an area and take note of whether we were able to find any stars there. This really helped the team learn about what the area looked like and gain a better appreciation for the species community along Port Orford’s coast.

Our team learned a TON this summer, especially the interns. Talia highlights her favorite new skill as being able to comfortably do scientific working dives in high surge, when at the beginning of the year, she was a brand-new diver. Katie said her favorite new skill was learning how to fill tanks for SCUBA diving. This was not only incredibly helpful for the team but also a great practical skill! Miles and Kersten had a really great experience this summer learning what it meant to be team leaders and running the day-to-day show of a very complicated experiment.

Once the team was done with the sunflower stars in the feeding experiment, they moved on to the portion of releasing them. This was a little more complicated than simply opening the cages and saying, “Be free, Willy!” Miles and Kersten were able to design a cage for all 24 of the stars to comfortably fit into. This cage was put down on the west side of Nellie’s Cove, rather than off the Hellbow. After all the stars were moved into their new hotel, all of the cement blocks and working materials were taken up to the boat to be cleaned later on.

After everything was set, a new experiment began: SuperNova! Yes, it’s as cool as it sounds. For this one, our team was doing similar surveys to before, but there was no kelp. After a few pre-surveys, we gave the sunflower stars a “get out of jail free” card and opened the cage. Once the doors were open and the stars were able to move freely, we tracked their movements over the course of about a week and made sure to simultaneously perform our normal urchin surveys to see how they would react. As you can imagine, this was a veritable explosion of sunflower stars in the area, and our team was having a blast. They all agreed that the coolest part was being able to see so many sunflower stars in the same place, when now it’s so rare to see even one.

SuperNova ended up taking our last little bit of the field season, and now our team is off to process all that data and start figuring out what it all means! In our initial analysis, we have seen evidence that our sunflower sea stars do, in fact, cause a halo effect. You might be wondering, what is a halo effect? This is when the stars are causing a shift in behavior, a certain radius distance away from themselves. We have seen that they are decreasing both urchin density and grazing to at least one meter away! Now imagine how many urchins we could scare away if we get a bunch more sunflower stars out there!

Most of our Pycnopodia ORKA team will be presenting at WSN (Western Society of Naturalists) conference this November, and we encourage you all to come and see some of our preliminary findings for the project!